|

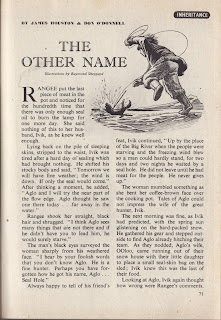

| Lilliput May-June 1951, p.71 |

In a previous article I showed Raymond Sheppard's illustrations for "The Riddle" by James Houston and Don O'Donnell. I thought I'd show the rest of the illustrations accompanying their other stories in Lilliput. Houston was born in Toronto in 1921 and died in 2005 but left a legacy for the Western world - his stories and appreciation of Inuit artworks. I'll say more on that below.

|

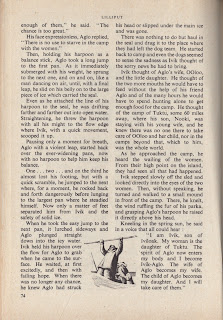

| Lilliput May-June 1951, p.72-73 |

"The other name" appeared in Lilliput May-June 1951 and is a tale of the Inuit and how they hunt seal for food and oil. The details are fascinating, how Aglo imitates the seal, popping up his head and then lying on the ice - ensuring the seal feels secure. However things don't go well for the hunters.

|

| Lilliput May-June 1951, p.74 |

|

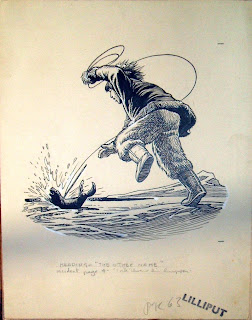

| "Ivik threw his harpoon" |

|

| "Plunged into the icy water" |

|

| "Tailpiece for "The Other Name" |

THE NEW LAMP

The next one appeared in Lilliput July-August 1951 and was called "The new lamp". We don't have the original artboards for this story, but it follows the adventures of Ivik-Aglo.

|

| Lilliput July-August 1951, p.71 |

|

| Lilliput July-August 1951, p.72-73 |

|

| Lilliput July-August 1951, p.74 |

THE JOURNEY INLAND

This story appeared in Lilliput February-March 1952 and wrongly gives James Houston's writing partner as Don O'Donnel [sic]

|

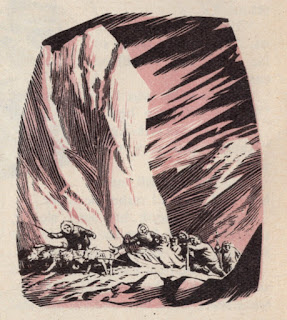

| Lilliput February-March 1952, p.72 |

|

| Lilliput February-March 1952, p.73 |

|

| Lilliput February-March 1952, p.74 |

The story concerns Tuktu, Ivik-Aglo's father-in-law and how he feels the cold and knows his memories are of earlier times when 'caribou took five days to pass through their camp' and they had enough to eat. He now decides to stay behind as the men go hunting and the women go to help. "He lay back on the sleeping robe and with a long sigh prepared to give up the fight with his lifelong enemy - the cold."

In the original art for p.74 (not shown) where Tuktu is dying it has an editorial addition stating "11⁄4" and the original art below for page 72 has "41⁄4" - the reproduction sizes expected. The indentation is there for the story title. Notice that the published images above have added colour which I think is because the corresponding pages in Lilliput in this issue are also coloured.

|

| Lilliput February-March 1952, p.72 |

I can't find any evidence these stories were reprinted from a book [UPDATE: See Below] but the fact the first two above are in the wrong order makes me think they might be. If you know do email me or comment here please. The only connection between these stories and "The Riddle" is the name Ikuma, but I suspect this is coincidence as none of the others are mentioned.

Since my last article mentioning James Archibald Houston, a biography has appeared called "James Houston and the making of Inuit art", by John Ayre and published by McFarland & Company, Inc., 2023 which gives me an opportunity to show Houston to you

The oldest book I could find written by Houston is 1965 - a good 14 years after the appearance of his Lilliput stories mentioned above. The 2006 book James Houston's Treasury of Inuit legends contains the following stories, none of which coincide with the Lilliput stories - except by virtue of being set around the Inuit: Tiktaliktak (1965); The white archer (1967); Akavak (1968) and Wolf Run (1971). The introduction mentions that he first flew into Inuit country in 1948 (which gives us a good date for the Lilliput stories). I was glancing through the memoirs Houston wrote in 1995 (Confessions of an igloo dweller) and thought this short summary might be of interest.

These memoirs of James Houston's life in the Canadian Arctic from 1948 to 1962 present a colorful and compelling adventure story of real people living through a time of great change. It is extraordinarily rich material about a fascinating, distant world.

Houston, a young Canadian artist, was on a painting trip to Moose Factory at the south end of Hudson Hay in 1948. A bush pilot friend burst into his room with the news that a medical emergency meant that he could get a free flight into the heart of the eastern Arctic. When they arrived, Houston found himself surrounded by smiling Inuit — short, strong, utterly confident people who wore sealskins and spoke no English. By the time the medical plane was about to leave. Houston had decided to stay.

It was a decision that changed his life, for more than a dozen years he spent his time being educated by those kindly, patient people who became his friends. He slept in their igloos, ate raw fish and seal meat, wore skin clothing, traveled by dog team, hunted walrus, and learned how to build a snowhouse. While doing so, he helped change the North.

Impressed by the natural artistic skills of the people, he encouraged the development of outlets in the South for their work, and helped establish co-ops in the North for Inuit carvers and print-makers. Since that time, after trapping as a way of gaining income began to disappear. Inuit art has brought millions of dollars to its creators, and has affected art galleries around the world.

In the one hundred short chapters that make up this book. James Houston tells about his fascinating and often hilarious adventures in a very different culture. He tells of raising a familv in the Arctic (his sons bursting into tears on being told they were not really Inuit), and of the failure to introduce soccer to a people who refused to look on other humans as opponents. He tells about great characters — Inuit and kallunait — who populated the Arctic in these long-lost days when, as a government go-between, he found himself grappling with Northern customs that broke Southern laws.

A remarkable, modestly told story by a truly remarkable man.

The biography (obviously written 10 years before he passed away) that appears at the back states:

JAMES HOUSTON, a Canadian author-artist, served with the Toronto Scottish Regiment in World War II, 1940-45, then lived among Inuit of the Canadian Arctic for twelve years as a Northern Service Officer, then as the first Administrator of west Baffin Island, a territory of 65,000 square miles. Widely acknowledged as the prime force in the development of Eskimo Art, he is past chairman of both the American Indian Arts Centre and the Canadian Eskimo Arts Council and a director of the Association on American Indian Affairs. He has been honored with the American Indian and Eskimo Cultural Foundation Award, the 1979 Inuit Kuavati Award of Merit, and is an Officer of the Order of Canada.

Among his writings, The White Dawn has been published in thirty-one editions worldwide. That novel and Ghost Fox. Spirit Wrestler, and Eagle Song have been selections of major book clubs. His last novel, Running West, won the Canadian Authors Association Book of the Year Award. Author and illustrator of more than a dozen children's books, he is the only person to have won the Canadian Library Association Book of the Year Award three times. He has also written screenplays for feature films, has created numerous documentaries, and continues to lecture widely.

Mr. Houston's drawings, paintings, and sculptures are internationally represented in many museums and private collections. He is Master Designer for Steuben Glass. He created the seventy-foot-high central sculpture in the Glenbow-Alberta Art Museum.

Houston, now a dual citizen of Canada and the United States, and his wife, Alice, divide the year between a colonial privateer's house in New England and a writing retreat on the bank of a salmon river on the Queen Charlotte Islands in British Columbia, a few miles south of Alaska, where he has written many of these memoirs.

I still can't find much on his writing partner, which is a shame, but what a fascinating man James Houston was.

UPDATE: 20 November 2023

John Wigmans found an article in Dutch which included a photo of Houston and wife but more importantly, he discovered that one of the four short stories was mentioned in the above biography. He sent me this screenshot and interestingly it mentions two of the four Lilliput stories (The New lamp plus "The Riddle), and that "[with] Don O'Donnell, he wrote a series of four stories for the Montreal weekend supplement "The Standard [i.e. I presume the Montreal Standard )

.jpg) |

| "James Houston and the making of Inuit art", by John Ayre, p.40 |